Hungarian national symbols: A connection between past and present

Change language:

Hungary has a rich and vibrant history, and over the years, our culture has acquired a number of symbols that reflect the cultural pride and remarkable heritage of the nation. Some of these Hungarian national symbols are well known to foreigners, while other symbols may surprise even the most seasoned traveller.

A symbol is more than just a representation of a concept, it also evokes the emotions and values associated with it. For example, the Hungarian national colours (red, white and green) are a highly respected emblem that resonates deeply with all Hungarians as a symbol of unity and national pride.

When discussing symbols and relics of the past, it is important to recognise that they can fall into several categories. These symbols can be either religious relics, literary artefacts, national emblems, or other cherished icons. Each of them serves as a strong link to Hungary’s heritage and identity. We consider such symbols and relics to be integral threads in the fabric of Hungarian culture.

The Hungarian national symbols

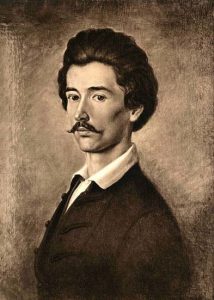

The first Hungarian National symbol which is known by many is the National Song, a powerful poem by Sándor Petőfi, written in 1848 just before the Hungarian Revolution kicked off on the 15th of March. Petőfi had originally intended to debut the poem at the People’s Assembly scheduled for 19 March, but as events took a dramatic turn, he recited it earlier, on the day of the uprising at the Pilvax Café. This moment transformed the National Song from a piece of poetry into a rallying cry for freedom.

The Hungarian Holy Crown is one of Europe’s oldest surviving crowns, a powerful emblem of Hungarian statehood that has been central to the nation’s history since the 12th century. Known as the foundation of Hungarian constitutional law from the Angevin period until the end of WWII, the ‘Doctrine of the Holy Crown’ recognised the crown not just as a symbol, but as a legal entity embodying the source of state power. According to tradition, King Stephen I consecrated the crown to the Virgin Mary in 1038, elevating it as a revered icon of Hungary’s sovereignty and spirit.