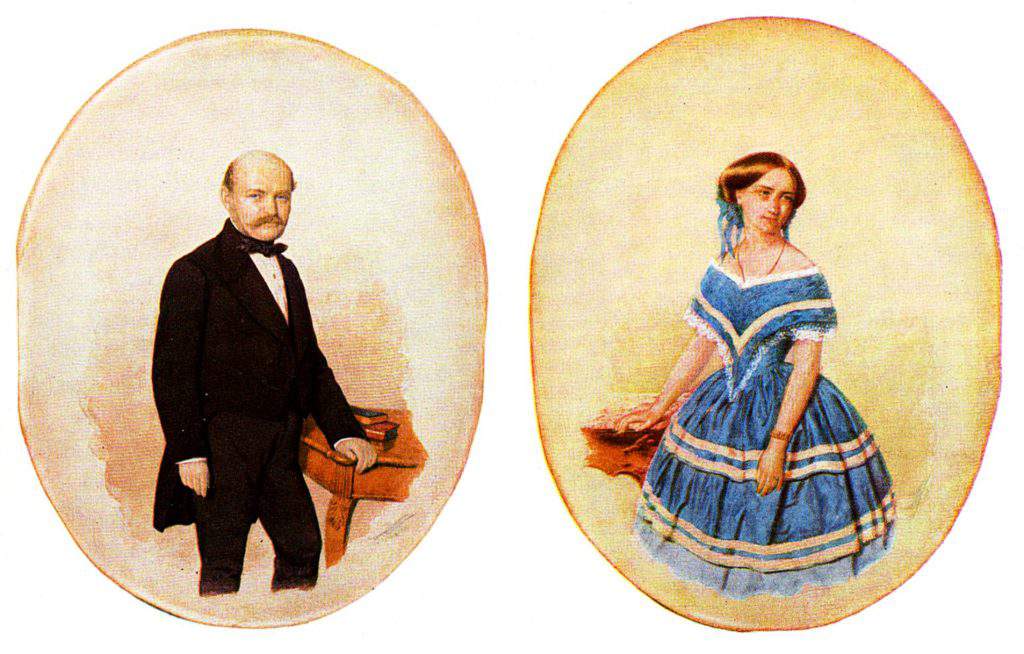

The Hungarian “saviour of mothers” who died a horrible death

Ignaz Semmelweis was a Hungarian physician of ethnic-German ancestry, known as an early pioneer of antiseptic procedures. He was described as the “saviour of mothers” since he discovered the cause of childbed fever (or puerperal fever) and introduced antisepsis into medical practice. The saviour of mothers later suffered from nervous breakdowns, ended up in an asylum, where he was tortured, and died a terrible death.

Born on the 1st of July 1818, in Tabán, which belongs today to Budapest, Hungary, he was the fifth child in a grocer family. He started studying law in Vienna, then changed track and switched to medicine. Semmelweis received his doctoral degree in Vienna in 1844 and was appointed assistant at the obstetric clinic in Vienna.

At the time, maternity institutions were set up all over Europe to address the problem of illegitimate children’s infanticide (i.e. the intentional killing of infants). They were gratis institutions and were attractive to underprivileged women, for instance, prostitutes. In return for the free services, the women would be subjects for the training of doctors and midwifes. Two maternity clinics were operating at the Viennese hospital, the First Clinic having a mortality rate of 10% and the Second Clinic with a mortality rate of 4%. Since the First Clinic had a really bad reputation, Semmelweis often heard women begging not to be taken there, and some even preferred to give birth on the street. Semmelweis was puzzled that puerperal fever was less frequent among those born on the street. Semmelweis proceeded to investigate its cause over the strong objections of his chief, who, like other continental physicians, had reconciled himself to the idea that the disease was unpreventable.

Semmelweis realised that the only difference between the two divisions was that the students were taught in the First Clinic, and midwives were taught in the second, so he put forward a thesis that students might have carried something to the patients they examined during labour. One of his friends died from a wound infection during the examination of a woman who died of puerperal infection. The similarity of the two cases supported his reasoning. He drew the conclusion that students who came directly from the dissecting room to the maternity ward carried the infection from mothers who had died of the disease to healthy mothers.

He instituted a policy of using a solution of chlorinated lime (calcium hypochlorite) for washing hands between autopsy work and the examination of patients.

The result was that the mortality rate in the First Clinic dropped 90%, and was then comparable to that in the Second Clinic. The mortality rate in April 1847 was 18.3%. After hand washing was instituted in mid-May, the rates in June were 2.2%, July 1.2%, August 1.9% and, for the first time since the introduction of anatomical orientation, the death rate was zero in two months in the year following the discovery.

In 1848, a liberal political revolution swept Europe and Semmelweis took part in the events in Vienna. After the revolution was put down, he found more obstacles in the way of his professional work: he was dropped from his post at the clinic and his application for a teaching post in midwifery was turned down. He returned to Pest in 1850 and worked in St. Rochus Hospital for 6 years. His measures reduced the mortality rate. In 1855 he was appointed professor of obstetrics at the University of Pest. He married, had five children, and developed his private practice.

In 1861 Semmelweis published his principal work, Die Ätiologie, der Begriff und die Prophylaxis des Kindbettfiebers (The Etiology, Concept, and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever).

He sent it to all the prominent obstetricians and medical societies abroad, but the general reaction was adverse. The weight of authority stood against his teachings.

He had a nervous breakdown in 1865. He had severe depression and became absent-minded. After a number of unfavourable foreign reviews of his 1861 book, he lashed out against critics in a series of Open Letters. His public behaviour soon became irritating and embarrassing to his associates. He began to drink and spent more time away from his family and his wife noticed a change in his sexual behaviour. He was referred to a mental institution in 1865, where he was severely beaten by guards, secured in a straitjacket, and confined to a darkened cell. Apart from the straitjacket, treatments at the mental institution included dousing with cold water and administering castor oil, a laxative. He died after two weeks, on August 13, 1865, aged 47, from a gangrenous wound, possibly caused by the beating. The autopsy gave the cause of death as pyemia—blood poisoning.

Semmelweis’ doctrine was subsequently accepted by medical science. His influence on the development of knowledge and control of infection was hailed by Joseph Lister, the father of modern antisepsis: “I think with the greatest admiration of him and his achievement and it fills me with joy that at last he is given the respect due to him.”

Featured Image: Wikicommons by npg.hu

Source: www.britannica.com