Change language:

László Almásy: The Hungarian man who served as an explorer, reconnaissance officer, and spy

A certain air of mystery surrounds the figure of László Almásy, and the release of the world-famous film The English Patient did little to dispel it. Almásy constantly pushed his own limits while becoming entangled in the events of World War II. Even among his contemporaries, he was something of a legend, but defamatory writings about him began to emerge early on, intensifying with the rise of the communist regime. An article by Ferenc Kanyó from Helló Magyar.

Passion for flying

László Almásy was born in 1895 in Borostyánkő (now Bernstein, Austria). Even at this early stage of his life, a minor legend formed around him—he was often addressed as a count. Although his family was of noble descent and bore the titles “of Zsadány and Törökszentmiklós,” they never actually held a count’s title. His grandfather, Eduárd Almásy, acquired Borostyánkő through purchase. According to one of László Almásy’s letters, it was suggested that his grandfather submit a petition for the title, which King Charles IV approved. However, Eduárd passed away before the process was completed, and his heirs never finalised the request in Hungary.

When Charles IV attempted to reclaim his throne, László Almásy took part in the events as the private secretary of János Mikes, the Bishop of Szombathely. (At this time, left-wing propaganda first accused him of homosexuality, claiming he was the bishop’s lover.) Since he had previously learned to drive, he often chauffeured key figures during important meetings, including Charles IV himself. It is uncertain whether he supported the king’s second return attempt. If he did, he remained silent about it, as the Horthy regime took harsh action against the participants of the second attempt, unlike the first.

Almásy had learned to fly while studying in Great Britain. His passion for exploration was likely inspired by his father, György Almásy, who travelled extensively in Asia. During World War I, he served on multiple fronts—first on the Eastern Front, then from 1916 on the Italian Front, and later in Albania. However, due to the restrictions imposed on aviation in Hungary following the Treaty of Trianon, he temporarily shifted his focus to automobiles.

Drawn to Africa

Almásy had already tested his limits with cars—he finished second in the Hortobágy-Balaton Tour and participated in numerous car races—but it was an African expedition that brought him true recognition. Accompanied by his brother-in-law, Antal Esterházy, he crossed the Libyan and Nubian Deserts in a Steyr automobile, travelling from Alexandria to Khartoum, the capital of present-day Sudan. Their 3,000-kilometer journey gained international attention, as they reached areas previously considered inaccessible by car. This achievement led to Almásy becoming something of a brand ambassador for Steyr, testing new models in the desert until the Great Depression shook the Austrian company’s financial stability.

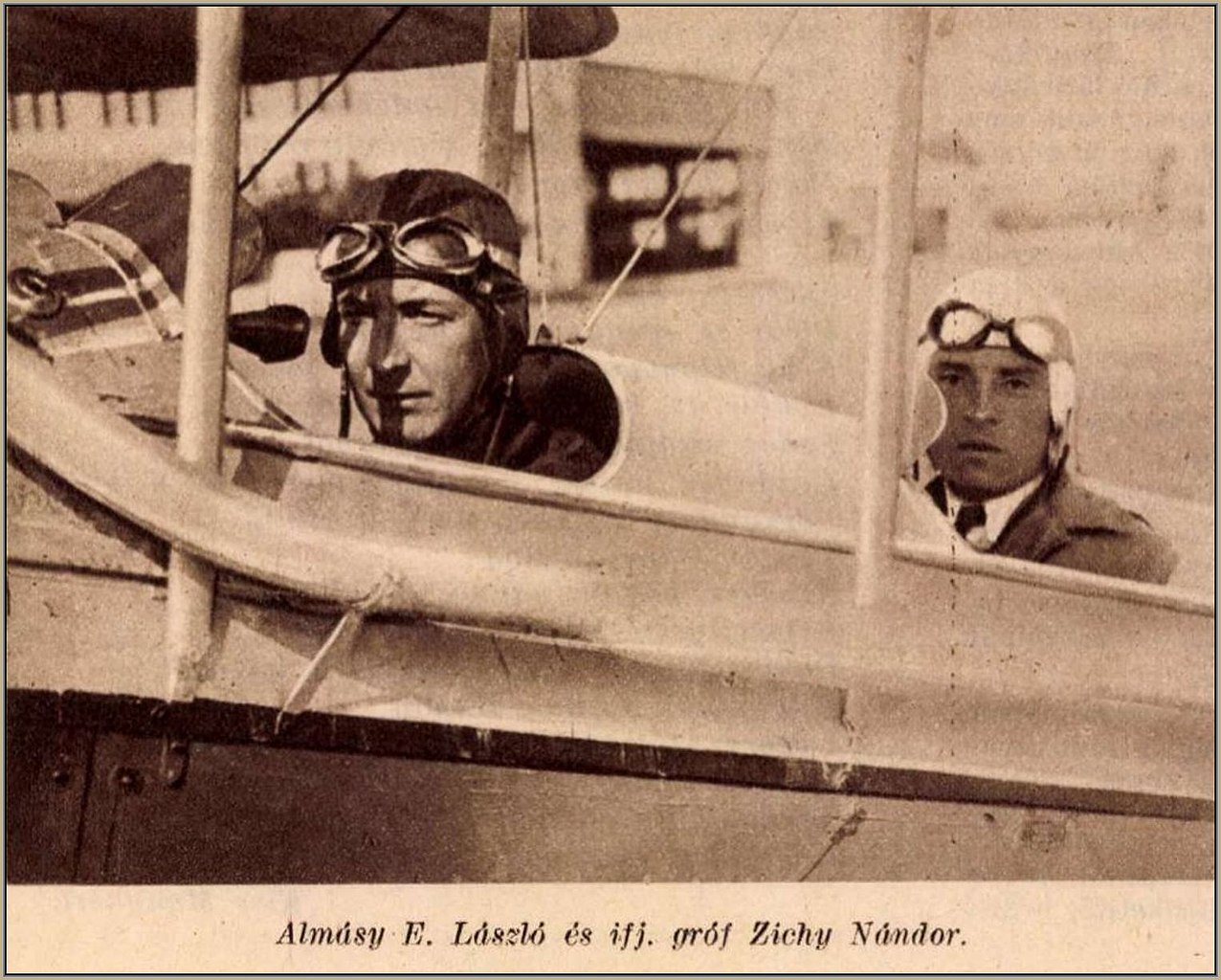

In 1931, he embarked on an aerial exploration with Nándor Zichy from Türkiye to Africa, but near Aleppo, their plane crashed, and the expedition they had planned to join proceeded without them. By 1932, however, László Almásy had reached the Zarzura Oasis. In 1933, with a sponsor backing him, he set off on another expedition with geographer László Kádár. In the Libyan Desert’s mesa formations, he made a groundbreaking discovery—ancient human and animal depictions. These paintings, which also portrayed plants and water, led him to conclude that the region had once been periodically or permanently covered by water. He remained in Egypt until 1939, returning to Hungary out of fear of British internment at the onset of World War II.

The war years

Almásy’s international fame became a burden during World War II, as the Germans recognised his expertise. Under pressure from the Abwehr, the Hungarian military assigned him to Africa, where the Wehrmacht needed individuals familiar with the local terrain for the Afrikakorps’ operations. Between February 1941 and August 1942, he served for a total of 570 days with the German 10th Air Division in Africa.

One of his first missions involved an attempt to extract Aziz Ali al-Misri, a nationalist politician sympathetic to the Germans, from Egypt. Almásy tried twice, but al-Misri was eventually captured by Egyptian authorities.

His most daring operation was infiltrating two German agents deep behind British lines. The mission was especially difficult because by then, the British had already cracked the Germans’ encrypted messages and were aware of the operation. Despite this, Almásy successfully smuggled the two agents into Egypt and safely returned with his team. He later recounted his experiences in With Rommel’s Army in Libya (Rommel seregénél Libyában).

Post-war persecution

Despite his wartime achievements, Almásy faced severe consequences after the war. He was first arrested in April 1945 and handed over to the Soviets, who transferred him to Austria in June but then released him. In July, he was arrested again in Szombathely by the Hungarian police, but after interrogation, he was freed.

However, in January 1946, he was arrested once more, released in March, and then detained again by the Soviets in June. He was handed back to Hungarian authorities in August. During his imprisonments, he was repeatedly beaten and tortured, yet no incriminating evidence was extracted from him.

Ultimately, his salvation came from an unexpected source—Gyula Germanus, a renowned orientalist. Although Germanus did not personally know Almásy, one of his students was Mátyás Rákosi, Hungary’s future communist leader. Rákosi signalled to the people’s court judge to hear Germanus’ testimony. Mistakenly believing that the orientalist represented the Communist Party’s stance, the judge acquitted Almásy.

In 1947, he was arrested again, but the intervention of the Egyptian king’s cousin and the British intelligence services saved him. However, he was forced to leave Hungary. Almásy settled in Cairo, where he worked as a flight instructor. He died in 1951 of dysentery.

A book on the traveller

A book about László Almásy’s life by Tamás Viktor Tari was recently published: The Father of the Sands: Almásy László’s secret life (A homok atyja. Almási László titkos élete) sheds new light on the fascinating and often controversial life of this Hungarian explorer, pilot, and wartime operative.

Read the original, Hungarian-language article HERE.

Read also: