A short history of the Hungarian hajdús with PHOTOS

In the second half of the 14th century, as Western Europe experienced growing urbanisation and a rising population, demand for meat surged dramatically. This led to large-scale breeding and export of Hungarian Grey Cattle. This economic boom gave rise to the hajdús—cattle drovers who herded, escorted, and guarded the livestock on their way westward.

The short history of the Hajdús

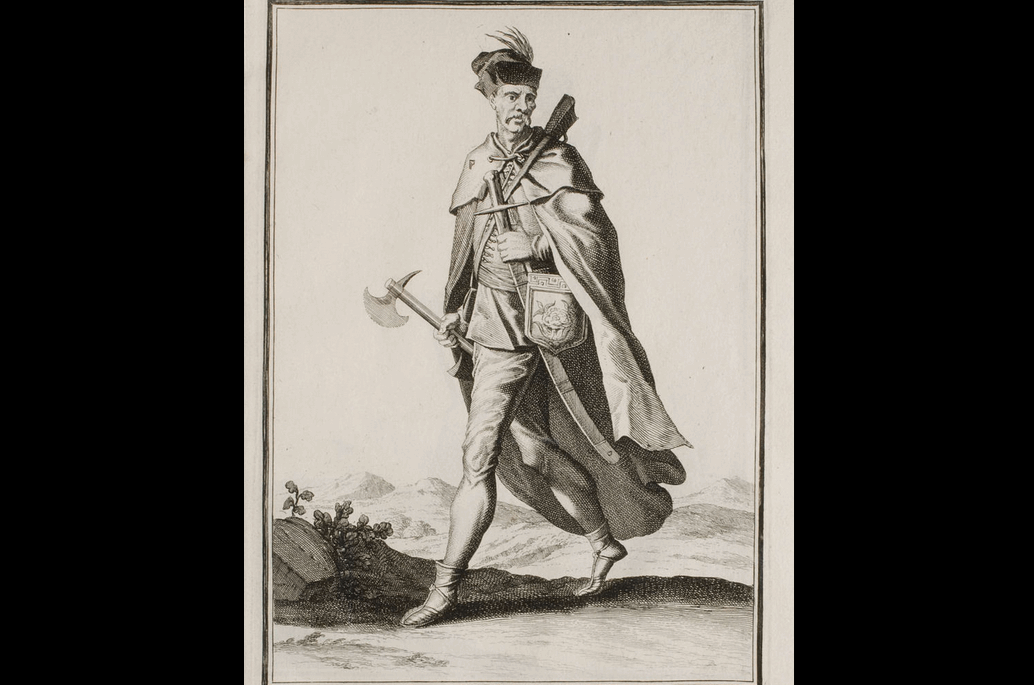

Initially, they were a mixed group: some were responsible for driving the cattle, while others followed the herds armed. According to widely accepted theories, their name likely stems from the Hungarian word for driver or drover, “hajtó” or “hajcsár.

Hajdús were generally hired as mercenaries or raiders for the duration of military campaigns, receiving either wages or shares of the loot. However, repeated pillaging and raiding prompted the enactment of numerous laws against them. Some hajdús served in private militias of landowners in exchange for acquiring certain free-peasant rights, while many others became border fortress soldiers. During the Fifteen Years’ War (1593–1606), large numbers joined the imperial army. From 1604 onward, they formed the core of István Bocskai’s rebellion.

Bocskai and the hajdús are inseparable in Hungarian history. He was the one who gave land and homes to these homeless and fugitive people. In his will, he entrusted them—once called “vagabond, degenerate Hungarians”—with the task of defending their homeland. At the time, public sentiment even referred to them as “Bocskai’s angels.”

Freedom fight with Hajdús

Relying on the hajdús’ weaponry, Bocskai achieved a series of swift and overwhelming victories, pushing back Habsburg control. On February 21, 1605, he was elected Prince of Transylvania, and on April 20, Prince of Hungary—a title later confirmed by Sultan Ahmed I. For a long time, it was believed that the Sultan and his advisors sent a royal crown to Bocskai in recognition of his success. However, a recently uncovered report from an envoy’s mission suggests it was actually Bocskai who requested the crown through diplomatic channels.

Overall, the campaign—particularly involving the hajdús and their Turkish-Tatar allies—inflicted devastating destruction across Hungary. As a result, the general population often saw them not as defenders of noble privileges or religious freedom, but as enemies. Most of the country’s population and influential leaders withheld support from Bocskai, and the resulting civil war largely served Ottoman interests. With all this in mind, one might fairly ask: can this otherwise successful revolt truly be considered a war of independence?

Hungarian historical memory retains a vivid and often polarised view of the hajdús. Late 19th- and early 20th-century nationalist historiography idealised them as champions of national independence and Protestant religious liberty. Even Marxist historians portrayed them positively, viewing the hajdús as a force representing both the transformative power of the masses and the class struggle of the working people.

With the settlement and colonisation of hajdú militias, seven so-called “Old” or “Great Hajdú Towns” emerged by 1608–1609: Böszörmény, Dorog, Hadház, Nánás, Polgár, Szoboszló, and Vámospércs—all located within the historical county of Szabolcs. Maintaining their privileges and autonomy brought frequent conflicts with both the county administration and the central government. By the late 17th century, they united their forces to establish the Hajdú District, an autonomous administrative unit with authority equal to that of the counties.

A significant number of Hungary’s fortified churches are located in hajdú towns. These structures served a dual purpose: providing local defense and functioning as part of the broader border fortress system. After the hajdús settled down, the urban layout of their towns was designed with security in mind, as protection against attacks and Turkish raids was a top priority. Hajdú towns featured a tripartite design—moving inward from the outskirts were the “latorkert” (outlaw zone), the “huszárvár” (cavalry fort), and the inner fortress—structurally mirroring the military fortresses of the era.

The fortress walls were integral to the inner fort and primarily protected the centrally located church. Typically surrounded by square defensive walls with loopholes and four corner towers, these churches often included separate watchtowers for early threat detection and defense preparations. Today, significant remnants of this fortification style can still be seen in Tiszavasvári, Hajdúnánás, Hajdúdorog, Hajdúszoboszló, and Hajdúszovát.

To read or share this article in Hungarian, click here: Helló Magyar

Read also:

- Timeless beauty in Budapest: How much do you know about Margaret Island? – read more HERE

- The astonishing story of Visegrád’s Salamon Tower, where Dracula was held captive: PHOTOS