177 years ago, Hungary surrendered to Russia: could our fight for independence have continued?

177 years ago, Lajos Kossuth, the governor-president who had fled to the Ottoman Empire, appointed General Artúr Görgei, then stationed near Arad, as dictator. Görgei decided to surrender to the invading Russian army to avoid further pointless bloodshed. But could the war for independence have continued? Was Kossuth right in accusing Görgei of treason and blaming him for the Russian (and Austrian) victory?

The Russian tsar left nothing to chance

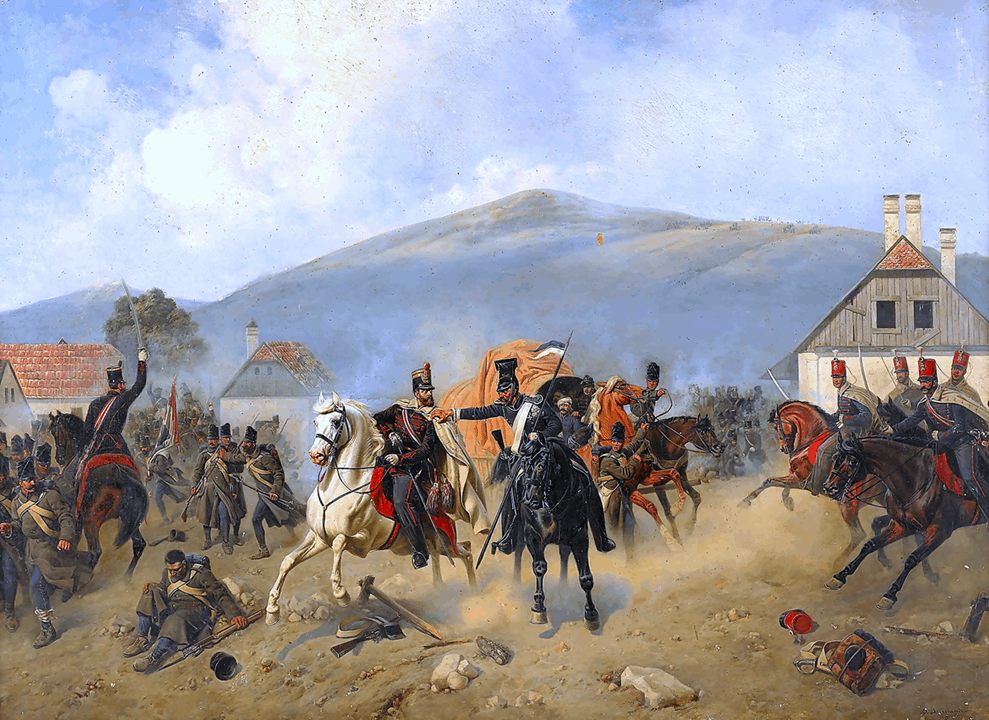

In the spring of 1849, Hungary’s hastily assembled national army racked up victory after victory, pushing imperial troops westward. Much of the country was liberated, and the Diet declared the Habsburg dynasty dethroned. But in December, newly seated Emperor Franz Joseph invoked an 1833 treaty and requested help from the Russian Tsar. Watching Austrian generals fail to suppress what he saw as “a handful of rebels” had shocked the Russian monarch.

Tsar Nicholas I understood that a Hungarian victory could ignite independence movements in Poland, which had already been partitioned. Determined to stop this, he sent a massive force, larger than the armies used in the Napoleonic wars, into Hungary. Led by Prince Paskevich, 200,000 Russian troops marched into the country, with another 80,000 standing by in the Romanian principalities and Polish territories. In 2022, Putin attempted to invade Ukraine with a similar number of troops.

Even by Kossuth’s own count in his accusatory letter from Vidin, the Hungarian army totalled no more than 140,000–150,000 men, scattered throughout the country in isolated formations (Görgei’s, Bem’s, and others). Opposing them stood the 170,000-strong Habsburg army commanded by Haynau, nicknamed the “Hyena of Brescia”, whose military skills exceeded those of his predecessors. Taken together, the Austro-Russian forces had a three-to-one advantage.

A startling military blunder

The Hungarians might have had a chance if they had taken on enemy forces separately. But Kossuth appointed Henry Dembinski as supreme commander, despite his prior failures. Dembinski made the baffling choice to concentrate troops around Temesvár, Szeged, and Arad, uncomfortably close to the Serbian uprising, and effectively abandoned vast stretches of Hungarian territory in the process.

While Görgei, despite suffering a serious battlefield injury, led his outnumbered troops on a flanking manoeuvre northward to join the main army, he arrived only to learn that Dembinski and Bem had already lost the Battle of Temesvár on 9 August. Görgei had earlier written to Kossuth, making it clear that without a win at Temesvár, where Hungarian forces actually had two-to-one superiority, he would be forced to surrender.

Kossuth read the report of the defeat, forwarded it to Görgei, appointed him dictator, and then fled the country. Historians view this as a deliberate transfer of responsibility, a move Kossuth made explicit in his now-infamous letter from Vidin on 12 September.

Görgei: Traitor to the fight for independence?

“I raised Görgei from the dust to win eternal glory for himself and freedom for his country. And he has cowardly become its hangman,” Kossuth wrote in the second paragraph of the letter. He mentioned Görgey’s name 43 times (using the aristocratic “y” spelling, which Görgei had abandoned in 1848 as a symbolic part of the revolution) and placed full blame for the uprising’s failure on his shoulders.

The stain stuck. Even decades later, in his old age and isolation in Visegrád, Görgei was asked why he hadn’t committed suicide. But according to his memoirs, taking his own life would have only confirmed Kossuth’s accusations. Instead, he refuted them by living a long life. Görgei died on 21 May 1916: the anniversary of his greatest triumph, the recapture of Buda in 1849. Since the late 1990s, 21 May has been celebrated as Hungarian Defence Forces Day.

Diplomatic dead ends

Could the war for independence have continued if Görgei had kept his army in the field against Haynau and Paskevich? Historian Róbert Hermann argues that resistance might have lasted a few more days or perhaps weeks, but without any realistic prospect of victory. The most that could be hoped for was some time for diplomatic intervention.

Yet no major powers, including Britain and France, were willing to step in. While they sympathised with the Hungarians, British policy prioritised preserving the Habsburg Empire as a counterbalance to Russia. London actually hoped the uprising could be quashed quickly, with minimal Russian involvement.

No foreign power ultimately supported an independent Hungary. Outside of fellow revolutionary Venice, only the United States was willing to recognise Hungary as a sovereign state. But by the time their diplomatic envoy from Washington arrived, Haynau was already preparing mass reprisals, despite contrary advice from the Russians. Tsar Nicholas I was reportedly outraged that the young Franz Joseph ignored his counsel.

Read also:

- Interested in Hungarian history? Rubicon launches free English-language website!

- Did you know Queen Sisi, Franz Joseph’s wife, had a tattoo? Or that she spoke Hungarian in secret? – read our article HERE

Read more history-related articles.

To read or share this article in Hungarian, click here: Helló Magyar