Hungary’s corruption rate and inequality is very severe compared to EU statistics

Change language:

The Hungarian economy is growing, and it is doing it quite nicely, but the benefits this bestows upon its citizens are becoming less and less evenly distributed in Hungarian society. Although the growth of the economy is needed, unfortunately, this growth model cannot be sustained for long. Meanwhile, the level of corruption has hardly been improving either. This is approximately how the European Commission’s latest country report about Hungary could be summarised, according to Index.

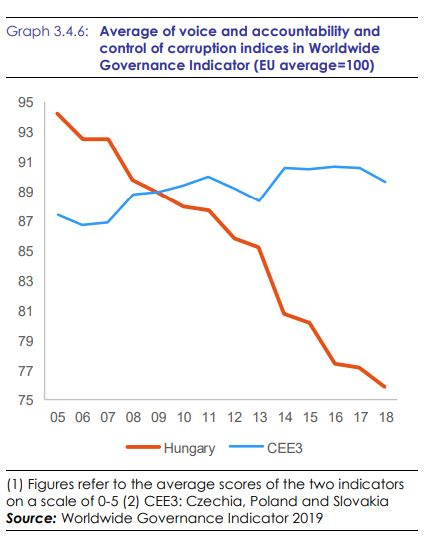

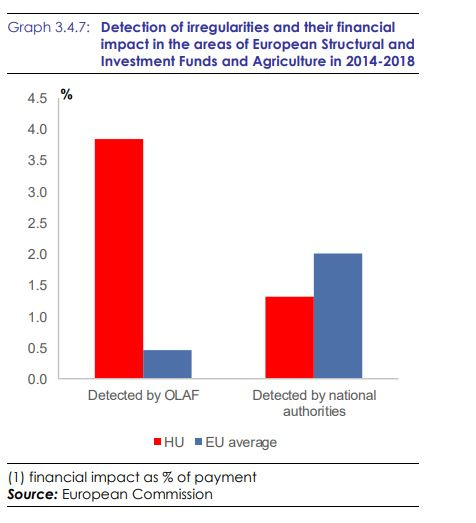

According to the European Commission, although the Hungarian government has accepted and implemented some of the recommendations from the 2019 country report – such as that

wages in the healthcare sector have increased, and Hungary has also spent more on research and development

– there are areas where there is no noticeable progress at all. This is especially true for filtering out corruption or guaranteeing judicial impartialness.

The economy is buzzing, but for how long?

The country report starts by acknowledging that the Hungarian economy has outperformed the EU average since the last country report.

The average Hungarian economic growth rate has been above 4% since 2014, and the overall slowing of the global economy due to the US-China trade war and some other uncertainties had no noticeable effect on Hungarian economy either.

The commission also recognised that Hungarian incomes have increased recently, the living conditions have improved, and poverty has decreased.

We wrote about the European Commission’s roadmap for EU members to combat climate change. It is worth keeping an eye open, as it was promised to be proposed this March. In January 2020, the European Commission officially registered the signatures for the Minority Safepack initiative. You can read about it here.

But the commission is concerned about how long this growth will last. According to the report, it will not last for long; the Hungarian growth model was mainly based on attracting more workers into production, while production did not become much more efficient and the output of the economy only grew modestly. Besides, because there will soon be full employment in the country, it will be harder to increase the number of workers.

Further complications come from inflation and the increase in production costs, causing the competitiveness of Hungarian exporters to decline. The government’s economic and tax policy is very pro-cyclical. This means that the government is supporting the economy when it is going well anyway, which means that

when Hungary does feel the global economic slowdown, the government will not be able to vitalise the economy.

GDP is on the rise, as is inequality

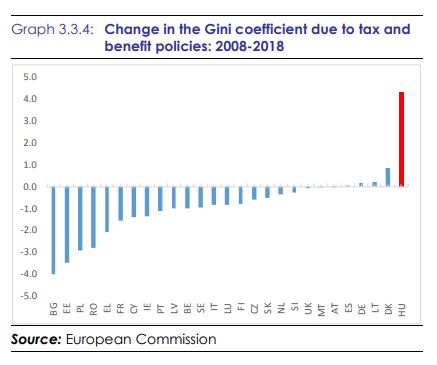

The commission explains in great detail that Hungarian society is in many ways quite unequal and has become even more so in the last decade. Although these inequalities within Hungarian society are not as high as in the EU on average, if there will be no change, then Hungary will soon catch up with the West.

In 2018, the wealthiest 20% had 4.4 times the wealth of the poorest 20%; the EU average of 5.17.

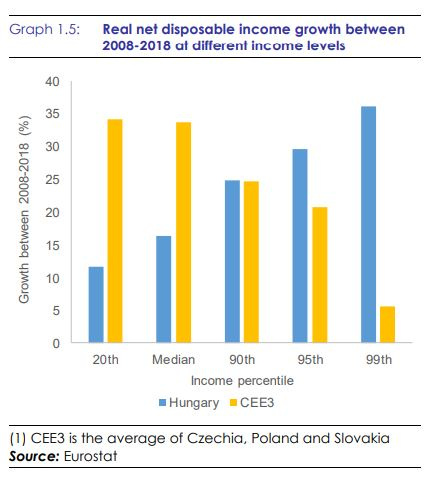

However, figures of the commission show that over the past decade, that the better income one had, the more their disposable income would grow.