Jobbik MEP Gyöngyösi: At the border of civilizations – Ten years of Turkey

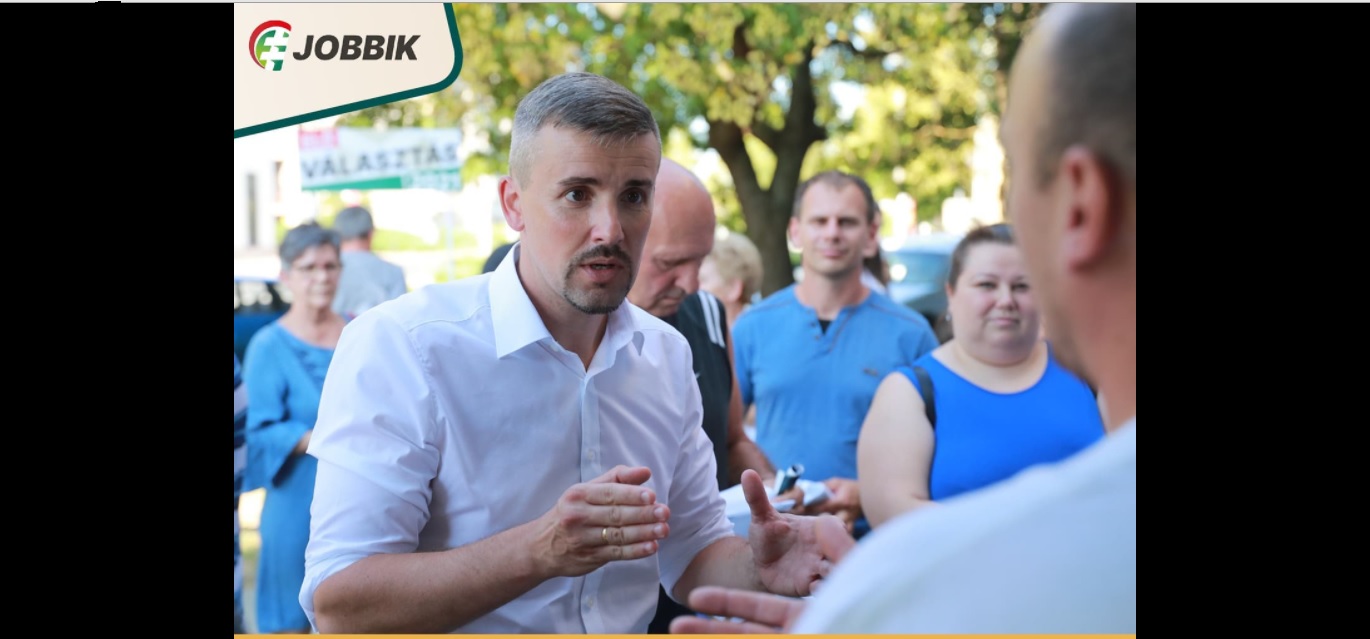

Remarks from Jobbik MEP Márton Gyöngyösi:

It is perhaps safe to say that Turkey is one of the world’s most exciting countries for any politician involved in foreign affairs. What is Turkey today? Located at the border of religions and the intersection of geopolitical interests, Turkey has been trying to carry out a daring social and cultural change for nearly a century. Where does all this lead to? Well, the question has never been more pressing than now.

Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has just managed to become the focus of international attention again – not that it’s so unusual for him. However, expelling the ambassadors of 10 major Western countries is a particularly harsh move even if Erdoğan eventually changed his mind and dropped the idea on the condition that the diplomats would refrain from “interfering with Turkey’s domestic affairs”.

But how could the Turkish situation escalate to this point? Back in the mid and late 2000s when I became active in politics, the Justice and Development Party (AKP) had just taken the power a couple of years before. Turkey had gone through difficult decades with constant tensions between the army, their favoured pro-West elite and the rural religious groups. This period of Turkey’s history was marked by military coups and civil unrest.

This was the background that saw the rise of the AKP, which promised democratization, economic liberalism and western norms while also supporting the religious feelings of the conservative societal groups.

Although the AKP was often accused of having a hidden agenda and heavily criticized for its Muslim religious convictions, I followed Turkey’s political events with great interest and optimism at the time. I was curious whether Turkey manages to synthesize the pro-West and Muslim ideas that were equally characteristic of the country. The first results were quite convincing, actually. Despite the global economic crisis, Turkey kept making progress and developed from a poor country with several third-world traits into a regional medium power. Although there were some suspicious signs, the country seemed for a long time to be able to manage the pressing cultural, religious and ethnic problems.

Perhaps we can now state that these goals were not accomplished and the changes at work since the mid 2010s clearly swept away the earlier achievements.

Starting out as a party intent on harmonizing Islam with a pro-West and pro-European progress, the AKP turned into a quasi party-state while President Erdoğan, who had risen from a rural, religious family to the political forefront, became a tyrant who uses the most brutal of means to subdue his opponents.

The Turkish currency dropped to a fraction of its value within a couple of years, and Turkey’s former diplomatic influence faded away: the country’s relations with its surroundings is highly controversial again. The fully state-controlled media spreads conspiracy theories while the Kurdish peace process came to a complete halt and has been in reverse ever since.

Seeing the president threatening Western European diplomats makes it painfully clear that Turkey’s political system has got to the point where this “populist foreign policy” is the last resort for the government to try and cover up such problems as the economic depression and the growing crisis.

In a functional democracy, the judicial system and the inherent checks and balances would likely have intervened long ago.

However, Turkey had only one check in its system: the army, the brutality of which was just as far from the European norms as the political forces it acted against. Turkey doesn’t seem to have arrived where it set out nearly a century ago. The question is: will it ever arrive?