Ferenc Kölcsey, the author of the Hungarian national anthem, was born 230 years ago

Change language:

On August 8, we celebrate the 230th anniversary of the birth of Ferenc Kölcsey, a Hungarian poet, literary critic, politician, and founding member of the Kisfaludy Literary Society. Kölcsey was the most outstanding poet to emerge within Kazinczy’s circle, and he is chiefly remembered today as the author of the Hungarian national anthem (‘Hymn’, 1823). In his oeuvre, the romantic elements mingle with classicist and sentimental features.

Early life

Kölcsey was born in 1790 in Sződemeter. He lost his parents at an early age and was handicapped by losing one eye to smallpox. These factors most likely contribute to the fact that he spent his school years in Debrecen in solitude and was known as a retiring youth with an intense, almost pathological love of books, Rubicon wrote. His imagination was occupied by the classics, particularly the deeds of Greek and Roman heroes. Later, Kölcsey turned his attention towards modern French writers: Bayle, Montesquieu, Regnard, Rousseau, and Voltaire, and German poets Bürger, Gessner, Goethe, Herder, Klopstock, Lessing, and Schiller.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons by Franz Eybl

Studies and poetry

In 1805, the young Kölcsey met Ferenc Kazinczy, the most prominent agent of the Hungarian language reform, at the funeral of Mihály Csokonai Vitéz. As a mentor and friend, Kazinczy helped the poet to develop his skills and talent. At the age of twenty, Kölcsey went to Pest for law school. During these years, he got acquainted with Pál Szemere, István Horvát, and Mihály Vitkovics. Kölcsey soon moved to Álmosd and then to Szatmárcseke where he lived in complete isolation with only books for company. He devoted his time to aesthetical study, poetry, criticism, and the defence of Kazinczy’s theories.

Kölcsey was fond of expressing abstract notions of beauty, ornamented by colourful adjectives, and he consciously experimented with structure.

The tone of his early poems is sentimental and self-torturing. In 1817, he wrote his first patriotic ode (“Rákóczi, hajh”), in which he reproaches public opinion for its apparent lack of respect for the historical past. “In the early 1820s, his poetry became increasingly concerned with patriotic themes because of his own disposition and his growing involvement in contemporary politics, which eventually led him to prominence in public life.

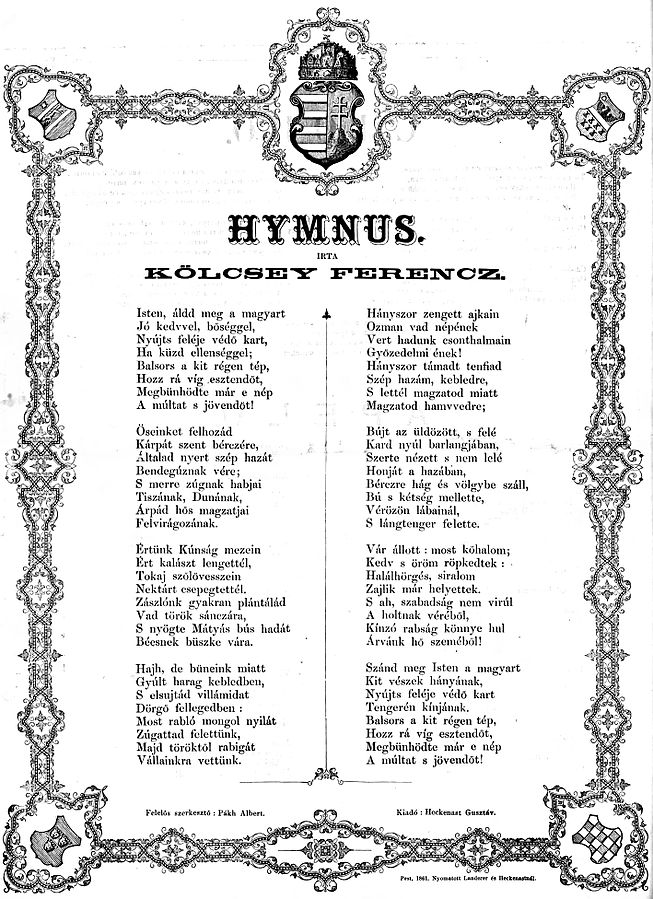

The most representative piece of his poetry, epitomising his views on Hungarian history, was the “Hymnus” (“Hymn”, January 22, 1823), evoking the glory of the early centuries – the Conquest and the reign of King Matthias – while presenting a morbid catalogue of national tragedies from the Tartar invasion and the Turkish occupation to anti-Habsburg rebellions which had been violently suppressed,”

wrote Lóránt Czigány in A History of Hungarian Literature.

Hymn, translated by Lőw Vilmos (Loew, William N.)

O, my God, the Magyar bless

With Thy plenty and good cheer!

With Thine aid his just cause press,

Where his foes to fight appear.

Fate, who for so long did’st frown,

Bring him happy times and ways;

Atoning sorrow hath weighed down

Sins of past and future days.

By Thy help our fathers gained

Kárpáth’s proud and sacred height;

Here by Thee a home obtained,

The heirs of Bendegúz, the knight.

Where’er Danube’s waters flow

And the streams of Tisza swell,

Árpád’s children, Thou dost know,

Flourished there and prospered well.

For us let the golden grain

Grow upon the fields of Kún,

And let Nectar’s silver rain

Ripen grapes of Tokay soon.

Thou our flags hast planted o’er

Forts where once wild Turks held sway;

Proud Vienna suffered sore

From King Matyas’ dark array.